(first published Guardian Weekend, 25th May 1996)

For the 14 years since he served in the Falkland Islands, KEN LUKOWIAK has struggled to understand his experience of war. This month he visited Argentina to talk to the people he’d met only in battle and, he hoped, to find the resolution he craves.

Mothers, Brothers, Buenos Aires and Me

On May 9th, 1982, a Thursday I believe, I turned 23. As birthdays go, it’s one I can look back on and remember exactly where I was, and who I was with, and where I was heading, for every second of the whole 24 hours. And yet ask me for a detail, or a conversation that took place, a meal I ate, even a card I opened – and it’s all gone.

Where I was was aboard the NV Norland, a North Sea ferry requisitioned from it’s owner, P & O, so that it could take me (and the rest of the Second Battalion of the Parachute Regiment) to the Falkland Islands.

“The where?” The Falkland Islands. One of the guys in B Company, who collected stamps before he joined the Cadets, said they were off the coast of Argentina. “Oh”.

14 years on, on May 9th this year – which was definitely a Friday – I turned 37. Where I was, was Buenos Aires, Federal el Capital of Argentina. The country of origin of the soldier’s who I had been heading towards aboard the MV Norland. Incidentally, every one of those soldiers knew exactly, as of day one of infant school, where their beloved “Malvinas Islands” were.

I was told before I travelled to Argentina, that the first sight that would greet me on the road out of the airport was a large billboard carrying words that, roughly translated, say: “The Malvinas belong to Argentina.” It turned out that this particular piece of information was a falsehood. The first billboard is for American Express, the second for Diners Club, the third for Mastercard, and so on. The Malvinas sign was actually a good mile or so from the airport and was a good eighth of the size of the advertising boards. Made me wonder.

The place I had to visit first in Buenos Aires, and naturally enough, was the memorial for the one-time infants who grew up to become the recent “just” deaths for the “Malvinas”. I planned to see it before I did anything, even before I checked into my hotel, and bar one cup of coffee and a sweet croissant in a corner cafe-bar. So it came to pass.

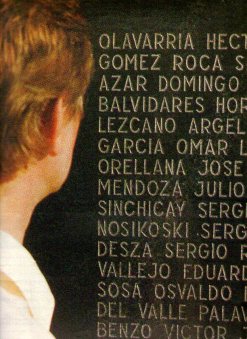

The memorial stands in the corner of a smallish city park, the Plaza San Martin. It’s main eye-catcher is a long, curved wall that holds 25 stone plaques that between them hold 649 names. On the left-hand side of the wall, above the plaques, is a metal-plate map of the islands, and above that, a flame, which I guess is meant to burn for ever and ever. Amen. In front, two armed soldiers dressed in combats, stand on guard. Opposite, a clock tower faces them which must make guarding the names the most tedious honour on earth.

Any wish I may have had of paying my respects to my fallen enemy in silent solitude, I soon realised was just that – a wish. The Plaza San Martin is surrounded on all four sides by at least eight lanes of traffic which swerve and toots and yells and curses itself from dawn to dawn.

I visited the memorial every day, and most nights. Every thought I pushed into my head while I was there led to a voice in my head telling me not to state the obvious. “War is wrong”. Don’t need to say it. “Man killing man is a crime”. Thought it a thousand times. “Why does it happen?” Why even bother asking any-more?

12 months earlier I had stood before another wall of names. Our wall, for “our boys” which stands looking out over the still waters around Port Stanley. It’s a curved wall, with names on, just like “their wall”. So similar are the two, you would think they were brothers. The only notable difference is that our wall has fewer names, and names that are raised above the stone, while in Buenos Aires they are carved into it. There are only 252 names on ours. Only. Which means that we won by over two-and-a-half to one.

When I walked our row of names, I looked for the ones I could build a memory around. I found Tam and Stevie P and Smudge and all of our Ruperts and even him that I’d never heard of before he bought it at Goose Green, Corporal. I touched each one. Slowly ran my fingers over them, like I was reading braille. Even shed a tear or two. Obvious again.

On a beautiful afternoon in the Plaza San Martin, I watched a very beautiful woman with long, coal black hair, walking the Argentine wall. She stopped at one of the stone plaques, fourth from the right, and remained motionless before it for a good five minutes. Then she reached out, touched a name, then stroked it. Like she was reading braille. And once again I go all obvious: “I did that”. She turned and walked away, past me and my Walkman, then sat alone, on the bench next to mine. For the next half-hour, between our questioning stares at the wall, we kept catching each other’s eye. I wondered what she wondered about me, and I wanted to go over and hear her story. Who was it? Was he your father, brother, husband, lover? Couldn’t have been son – you’re too young. I looked and made to get up and then stopped and sat down again and looked some more and thought again about going over – but I couldn’t. What could I say? “Sorry about that.” Even though I really truly was. Naturally enough.

A big surprise for me was just how European the people of Buenos Aires look. Because when I first got to Goose Green and saw row after row of Argentine prisoners, once past the initial “Fuck, there’s thousands of the bastards”, the next thought was how Indian they looked, how Mayan they looked. Not all of them, but certainly the vast majority.

Yet in Buenos Aires I hardly ever saw a face that looked remotely Indian. Couple of beggars, the odd street-vendor selling phone cards or disposable lighters. But none of the shoppers. None of the of the people sipping expensive cappuccinos in the stylish cafe-bars.

Then one night, at 3am, I paid my fancy drinks bill and set off for home. The street-cleaners were out then, and the garbage collectors, and whole teams of people, families for sure, were searching through black plastic bags which contained the waste left by the row after row of shops that sold Cartier watches and Armani suits, and any other luxury item that will do nicely sir. And I wondered, as a percentage, how many sons of the expensive-suit owners of Buenos Aires, got to give their all for “Argentina, Argentina, Argentina”, in the Malvinas war. About as many as get to clean the streets was my conclusion.